Britain’s Owls

Short-eared owl hunting along the roadside, North Uist, Outer Hebrides

Short-eared owl hunting along the roadside, North Uist, Outer Hebrides

Many people, including non-birders, love to see owls and where you live will influence what you have a chance of seeing.

The Tawny Owl is Britain’s most numerous and widespread species. Think of a ‘hooting’ owl call and it will be this species but the female has a ‘kee-wick’ type of call too. They usually nest in tree holes and woodland is their preferred habitat although they can find other places to nest. They have even been known to nest in peoples’ gardens in specially erected nesting boxes.

Tawnies can be quite aggressive in protection of their nest sites and have even attacked humans when they have unfledged young (pioneering bird photographer Eric Hosking was attacked when going to his hide to photograph one for instance. He lost the sight of one eye!) so if you are photographing one at the nest, beware and wear eye protection at least! Young will leave the nest before they are fully feathered and often end up on the woodland floor. If you happen to find one in this situation, do not pick them up and take them home thinking they are abandoned. Perhaps put them up off the ground in a tree to keep them away from ground predators or other well-intentioned people (beware their sharp talons). Then walk away. Their parents will come along and feed them once the sun has set.

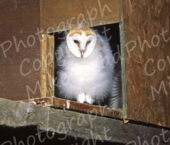

Around sunset and sunrise is probably the best time to stand a chance of encountering our most loved owl, the Barn Owl. Watch this species from a distance especially if you know where they are nesting as they are given special legal protection, (they are a ‘Schedule one’ species) and disturbing them at the nest or with dependant young could land you with a very heft fine or even 6 months in prison. Barn Owls are the ghostly white birds you might catch a glimpse of in your car headlights if driving home late on a calm, dry evening. While doing photography on the Somerset Levels for one of my illustrated talks, my wife and I saw a pair of owls hunting in broad daylight at about 3.30pm. We stayed and watched them hunting for some time but as the light faded, we decided to leave. During the 2-hour drive back to Ringwood we glimpsed yet three more Barn Owls, a fabulous end to an enjoyable day.

A really unexpected owl-in-the headlights sighting was of an owl that I saw close to home at about 10pm one winters evening. I glimpsed a ‘brown’ owl as I drove along and identified it as a probable Tawny. However, as my two passengers had not seen it I turned around and went back to see if it was still there. Imagine my surprise when it was still there and it was actually a Long-eared Owl! This species is the most difficult of our five ‘regular’ owls to see, especially here in the south of England, but in winter there is often an influx of Long-eared Owls from the Continent as they grey to escape the colder conditions there. Sometimes there can be as many as 20 roosting in thorny hedgerows, especially in East Anglia. However my only successful photography of the species has been in Hungary where there was a ‘town roost’ of over 40 birds!

Their close relative the Short-eared Owl often hunts rodents during daylight. They rely, like all the other UK owls mostly on silent flight and acute hearing to locate their prey. By the way, the tufts on the top of their heads that give S-e Owls and L-e Owls their name has nothing to do with their ears which are on the sides of their heads. Short-eared Owls mostly breed in upland areas of northern England and Scotland and on some of the Scottish islands but move to lower lying rough grassland for the winter months. Again, there is often a winter influx from mainland Europe but the quantity arriving varies greatly from one year to the next.

Little Owls feed on worms, beetles, moths and other insects. Like Barn Owls in particular, they can suffer high mortality rates during prolonged cold spells or wet weather during the winter. Since their introduction in the 1800s their numbers have fluctuated but in recent years, it is possible their decline in numbers could be linked to the 50% decline we have seen in insects in our countryside.

Two other owl species occur in Britain. From 1967-1975 a pair of Snowy Owls nested on Fetlar in the Shetland Islands. Occasional ‘Snowies’ show up in Britain in the northern isle or in the Cairgorms and in 2022, a long-staying bird moved from St Kilda to North Uist. Sadly I have no photos of ‘Snowies’.

Eagle Owls are now nesting in Britain, I think in Yorkshire and other parts of northern England. Their origin is open to much speculation; some say they are from escaped/released falconer’s birds while others believe they have colonised naturally from mainland Europe.

Owls really are a beautiful family of birds well worth seeing in all of their guises. Like much of our wildlife, they need more sympathetic land management to thrive and regain their former numbers.